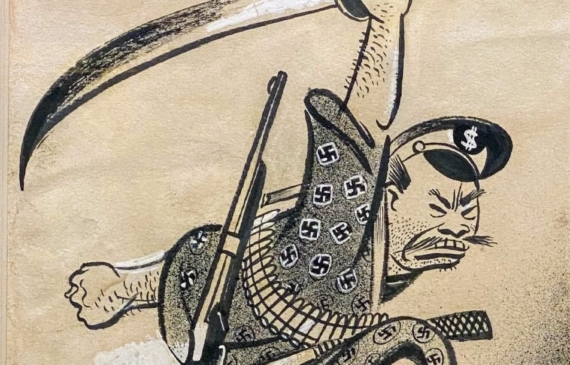

William Gropper

William Gropper

American, 1897 – 1977

Hirochito

Mixed Media on paper

10 ½ H. x 8 ½ W. inches

Perhaps Gropper’s most infamous drawing from this period, one that caused an international fracas, appeared in Vanity Fair in August 1935. The cartoon was part of a series suggested by editor Frank Crowninshield in which several impossible situations would be depicted, including William Randolph Hearst becoming American ambassador to the Soviet Union, the King of Italy berating Mussolini, or Japanese Emperor Hirohito being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The Italian drawing was dropped from the group-a letter from Crowninshield to Gropper indicates concern that Vanity Fair could lose significant business from Italian concerns-but the one of Hirohito was published, and it deeply offended the Emperor and the Japanese government, which demanded an apology. The drawing shows the Emperor decked out in medal-encrusted military regalia, pulling a rickshaw-like cart on which an oversized scroll is carried. The scroll ostensibly represents the Peace Prize, but its form and size combine with the wheels of the cart to make it appear that Hirohito is dragging a cannon behind him. The bellicose actions of the Japanese in mainland Asia, including the invasion and occupation of Manchuria, had brought their warring activities into public discussion well before Japan’s entry into World War II.

Gropper refused to apologize for his drawing, and U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull had to explain to the Japanese that he had no control over the press. The Japanese retaliated economically, applying pressure to advertisers in Vanity Fair, and this eventually brought about the demise of the publication. The unrepentant Gropper repeated much of the cartoon’s imagery, in a December issue of the New Masses. Here Hirohito wears a single, swastika-bearing medal and pulls another cart, this time with an armed skeleton riding on it, across Manchuria and into China.

Artist Description

William Gropper was a painter and political cartoonist who is best remembered for his striking social commentary. He was born in 1897 on the Lower East Side in New York City to a large, poor immigrant family. Due to the family’s financial difficulties, Gropper was forced to leave school at a very young age and work in a garment sweatshop with his mother and siblings. Several years later, he enrolled in art classes at the socially progressive Ferrer School where he received instruction from noted Ashcan artists Robert Henri and George Bellows. Gropper later recalled the influence of these men saying, “Right then, I began to realize that you don’t paint with color—you paint with conviction, freedom, love and heartaches, with what you have.”

Following his time at the Ferrer School, Gropper continued his education at the Chase School, later known as Parson’s School of Design. After graduation, Gropper briefly illustrated for the New York Tribune, during which time he began contributing to socialist publications, such as The New Masses, Labor Defender and The Nation. In 1924, he began a long career as a regular cartoonist for the Freiheit, a left-wing Yiddish daily newspaper.

As his career progressed in the 1930s, Gropper turned his attention more towards painting. In addition to the early influence of Henri and Bellows, he also looked to Cubism for inspiration and incorporated sharp angles and exaggerated figures in his paintings. In the 1930s and 1940s, Gropper completed several murals for New York businesses, and for post offices in Detroit and on Long Island. In 1937, Gropper was awarded a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship which he used to travel to the Great Plains and to the Southeast. In 1942, he painted Field Workers, based on sketches made while in the South. It was completed during the height of his career as a painter and the saturated coloring and exaggerated angles are characteristic of his mature painting style.

Though Gropper worked in different mediums his subject was always people, and he is often referred to as “the workingman’s protector.” In an interview, Gropper explained his motivations for exposing the wrongs committed against workers, “That’s my heritage. I’m from the old school, defending the underdog. Maybe because I’ve been an underdog or still am. I put myself in their position. I feel for the people . . . I become involved.”