SOLD

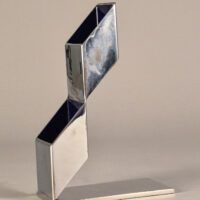

Beverly Pepper (American, 1922-2020)

Untitled, c. 1970

Steel and enamel

6 H. x 6 ½ W. x 4 ¾ D. inches

SOLD

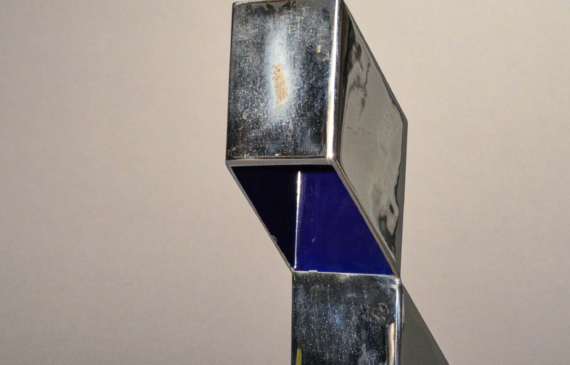

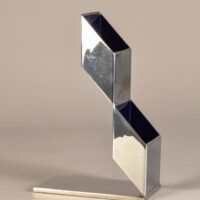

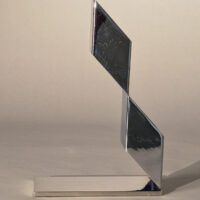

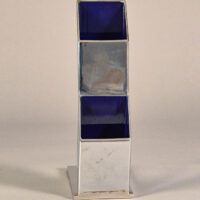

Beverly Pepper (American, 1922-2020)

Untitled, circa 1965-1970

Steel and enamel paint

11 ¾ H. x 8 W. x 3 ¾ D. inches

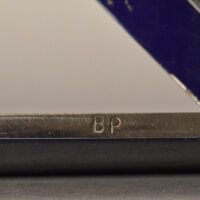

Stamped: BP

A formidable opponent of the status quo, Beverly Pepper took on industrial sculpture at a time when many women were unfamiliar with how to operate power tools. Born in Brooklyn in 1922 to the children of Jewish immigrants, Pepper was never told that there would be roadblocks in her future simply because of her gender. Her mother never imposed the idea of necessary femininity on her daughter, so it likely came as a shock to the young artist when she was removed from an industrial design course during her first year at Pratt University at 16 years old because the school decided that she was not capable of operating machinery as a woman. Despite this hiccup, the exposure to the course while she was enrolled sparked a lifelong interest in the industrial arts that would resurface later in life. From there, Pepper turned to painting and went on to study at L’Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris, where artists like Giacometti, Modigliani, and others had studied. During this time, Pepper met and married her husband Curtis Bill Pepper, moving to Italy for his work in the 1950’s. She settled with her family in the country, where she maintained a studio in Umbria until her death.

It was not until 1960 that Pepper shifted her focus to sculpture after a visit to Angkor Wat in Cambodia, forever moved by the relationship between temple ruins and the accompanying overgrowth from the surrounding jungle. She debuted her sculpture with an exhibition of carved tree trunks in Rome two years later, and soon after was invited to participate in a festival in Spoleto – the only catch being that she was asked to provide works on metal, and she did not know how to weld. Convincing a local ironmaker to teach her how to weld, she produced works for the Spoleto show and was one of only three women that were exhibited alongside great sculptors like Alexander Calder and Henry Moore. After that show, she was invited to work in a factory in Northern Italy and never looked back, finding the factory an ideal place to create the large scale sculptures she is so well known for today. This venue of choice, the factory, was quite a boys club – Pepper was the only female in the building much of the time, and frequently had to use the men’s restroom as there were none designated for women. While working at a US Steel factory in Pennsylvania, the company suggested she try out their new material: Cor-Ten steel. Pepper asserts that she was likely the first artist to work with the material, one that became a favorite in her own sculptures. Her studio in Italy was a converted aircraft hangar, allowing for the massive constructions and manipulations that she envisioned.

From monumental sculpture, Pepper advanced into land art during the 1970’s, creating earthbound pieces that interact with her sculptures just as the jungle was a part of the architecture at Angkor Wat. Although she claims not to be spiritual, she has focused her work on ideas of the urban altar and the totem/obelisk, letting her sculptures convey a sense of place that borders on the sacred. Her work can be found at numerous outdoor venues, including New York’s Storm King art center, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, and many more.